Module 7: Equity, Diversity & Inclusion

DEI vs. EDI | Why EDI? | Why EDI? Pt. 2 | Student Affirming Pedagogies | Assignment & Discussion

Why EDI?

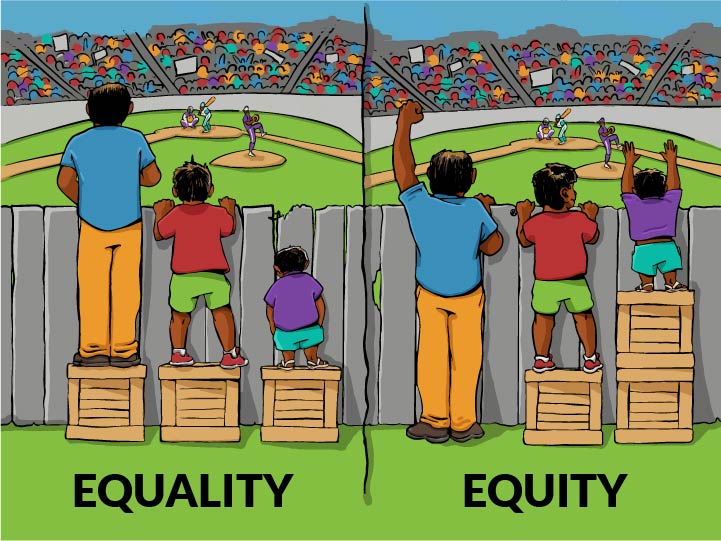

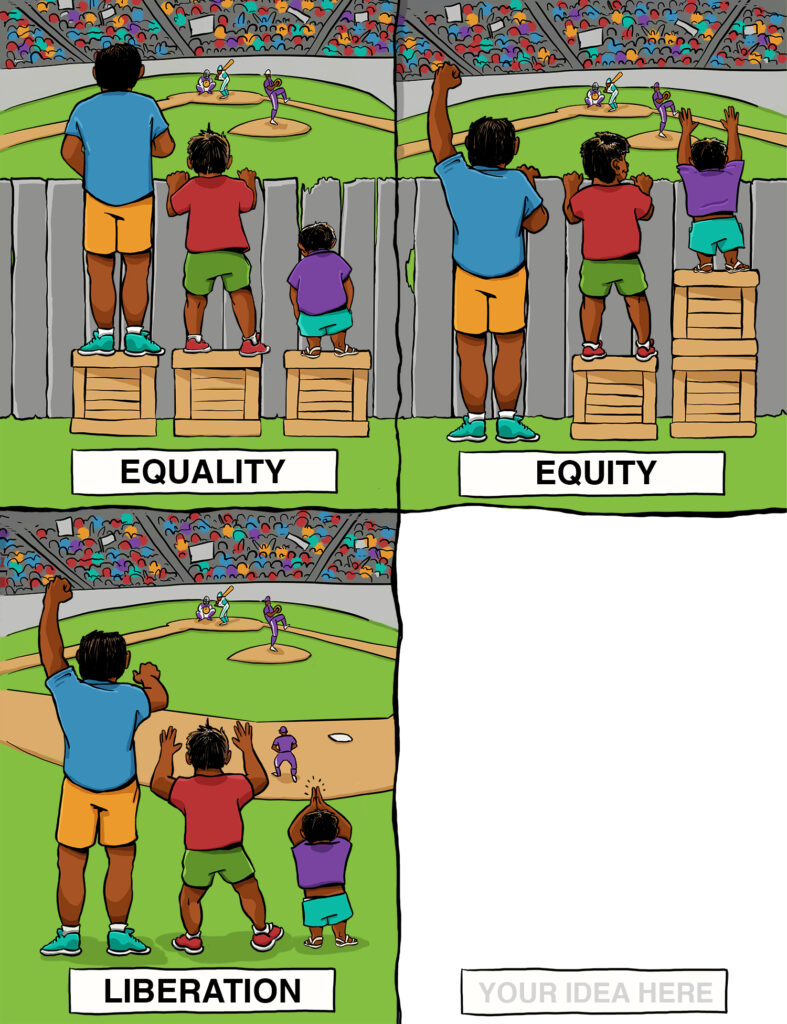

Equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) is a more proactive and robust way of addressing the marginalization and oppression in society. You may have encountered versions of the image below that intend to explain the significant difference between equality and equity. Notions of equality tend to ignore obvious and documented limitations different groups historically and currently experience. Equal opportunities are not truly equal since different members of different groups face challenges specific to their multiple identities.

EDI attempts to redress the intentional and unintentional ways individuals have experienced oppression due to their identities. This can and should occur on a contextual basis and is why a nuanced recognition and understanding of history/ies, how identities and socio-political power functions is critical to make the most equitable choices in any given situation. EDI recognizes that full equity for all might be an impossible reality to achieve and sustain but efforts can always be made to move towards that goal, and that certain groups have been intentionally and historically disadvantaged to benefit others.

Affirmative action is a prime example of attempts to legally enforce equity, though because of the enduring and unshifted dominant structural forces, the policy has been difficult to enforce, dysfunctional, repeatedly attacked and in many ways, effectively dismantled through the recent Supreme Court ruling that removed race as a category to consider during college admissions. EDI ensures that centuries of legalized oppression like structural racism, sexism, and class privilege cannot be ignored.

Over the past few years, critical race theory (CRT) has gotten a terrible rap, and has even been outlawed in certain states. Yet the premise is based in a simple recognition of the historical injustices different racial groups have experienced and the laws used to oppress them in the United States. Laws and policies are clear ways to identify which groups are advantaged or disadvantaged, and a group of law students and scholars in the 1980s became significant contributors to legal theories of racialization, continuing in the long line of advocacy that abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, and the Lyons family; Black feminists like Sojourner Truth, Barbara Smith and the Combahee River Collective; sociologists like W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells; and lawyers like Paule Murray and Thurgood Marshall had argued for centuries. Derrick Bell and many others were part of the working group that established critical race theory as a legal field. Kimberlé Crenshaw in particular has been noted for coining the term “intersectionality” though many Black women have been highlighting their multiple identities and the oppression they face as a result of these inseparable and equally significant experiences for centuries. Crenshaw’s case defending Black women at General Motors highlighted the specific discrimination these women faced as they were unable to receive the protections that Black men received (race) or that white women received (gender). There was no policy that addressed their specific experience, but they were being treated differently as, and because they were Black women.

Intersectionality goes far beyond simply gender and race, and is a lived reality for all people, whether they are forced to confront oppression daily or infrequently, and whether they face oppression for one, a few, many, or all of their identities.

Though it’s often overlooked and ignored, It’s also important to recognize how oppression and privilege shift from context to context. Even historically marginalized groups can become dominant if they are the majority in a given situation. However, this “flip” in power dynamics does not minimize or erase the historical and/or pervasive social, legal and economic structure. This is why you may have heard controversial statements like, “a Black person cannot be racist.” While the Black person can exhibit extremely prejudiced and even violent behavior towards white or people of other races, this is a largely individual act that does not erase the historical fact and legacy of chattel slavery and anti-Blackness in the United States, much less around the world. It’s important to be able to distinguish between individual and personal acts of oppression/”ism’s” vs. the larger structural forces. However, it’s also important not to minimize the violence and ignorance of a person’s ideology and behavior, as the term racist means to believe one’s own group is superior to others and to dislike or even hate others simply because of their race.

Race is a social construct and not a provable biological or genetic fact, but how has and does our society function? Take a look at the world around you, at who lives and works where, at who is protected and who is penalized, at who is represented politically and where the power resides. Race, just like gender and other identities are social constructs, but they have very real and serious impacts on people’s lives every day, their pasts, and all of our futures.